Detention of Rohingya Refugees Challenged in Supreme Court: Rights vs. Sovereignty in a Stateless Dilemma

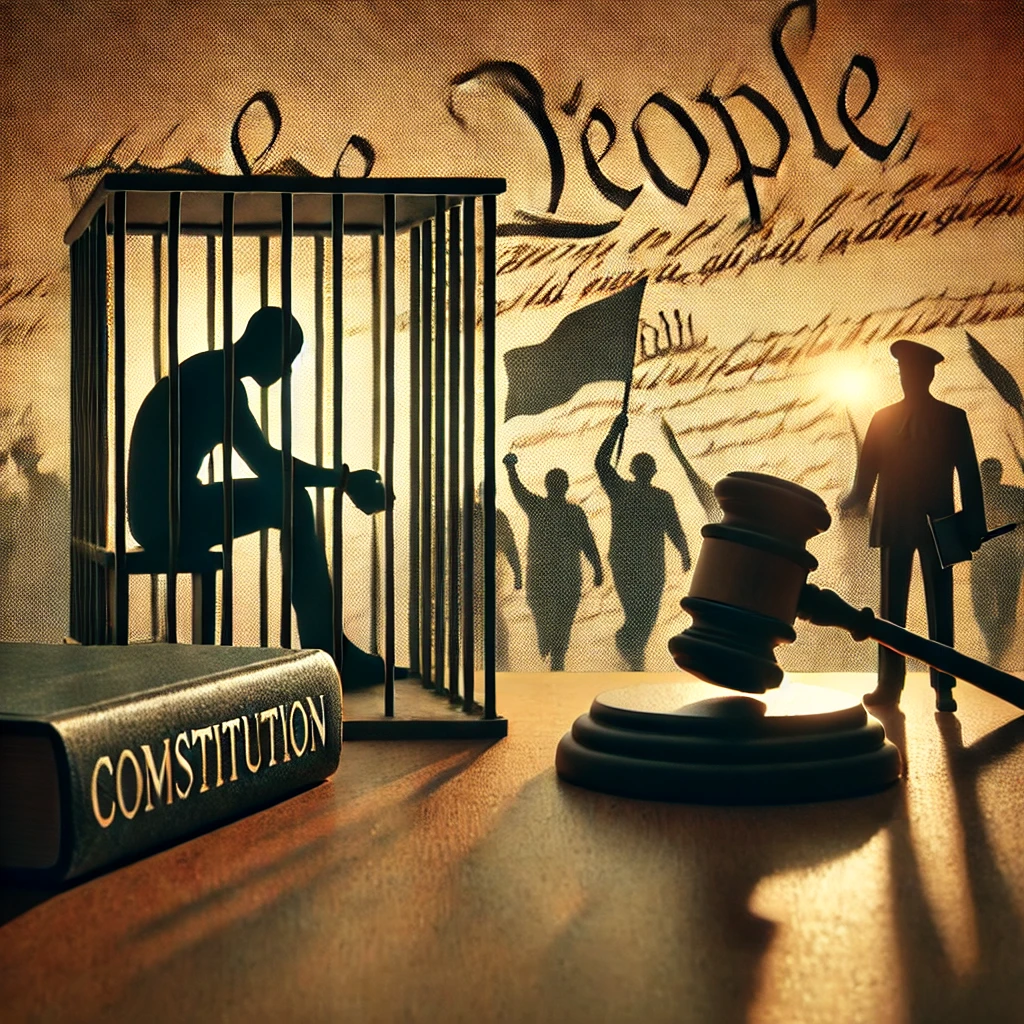

In a case that tests the boundaries between human rights and national sovereignty, the Supreme Court of India is hearing a petition challenging the prolonged detention of Rohingya refugees, many of whom have been incarcerated in detention centers across various states without trial, charge, or repatriation.

The petition—filed by a coalition of civil rights lawyers, refugee rights organizations, and concerned citizens—seeks urgent intervention against what they call an “undeclared policy of criminalizing statelessness.”

At the heart of the matter is a deep moral and constitutional question: Can India, a signatory to several international human rights conventions, detain people indefinitely for simply fleeing persecution?

The Background: Who Are the Rohingya?

The Rohingya are a stateless Muslim minority from Myanmar’s Rakhine state, many of whom fled after facing genocide-like violence and ethnic cleansing at the hands of the Myanmar military. The UN has described them as “the most persecuted minority in the world.”

Since 2012, over 40,000 Rohingya refugees have entered India, settling in makeshift camps in Jammu, Hyderabad, Delhi, and Mewat. Most arrived with no documents, driven by fear, hunger, and a desperate search for safety.

India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and hence, does not have a codified asylum law. As a result, refugee protection is governed by a patchwork of court judgments, executive notifications, and UNHCR interventions.

The Petition: Demanding Constitutional and Human Protections

The PIL in the Supreme Court challenges the detention of over 250 Rohingya individuals, including women and children, who were picked up during identity verification drives and labeled as “illegal immigrants.”

Petitioners argue that:

- Detention without trial or deportation violates Article 21 of the Constitution (Right to Life and Liberty).

- India is bound by the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits sending refugees back to countries where they face persecution, as part of customary international law.

- The state has a duty to process refugee claims individually, and not treat all Rohingya as a monolithic threat.

- Children and women must not be held in jail-like detention centers for prolonged periods, especially without being charged with a crime.

Government’s Response: Security and Sovereignty First

The Central Government has maintained a firm stance, arguing that:

- Rohingya refugees pose “national security threats”, citing alleged links with terror outfits (although no formal charges exist against most detainees).

- India has the sovereign right to control its borders and regulate the presence of non-citizens, especially undocumented individuals.

- The UNHCR refugee card is not legally binding, and cannot override India’s immigration laws.

In 2021, the Union Home Ministry issued a statement asserting its intent to deport Rohingya refugees, sparking condemnation from international human rights groups.

Legal Landscape: What Courts Have Said So Far

- In Mohammad Salimullah v. Union of India (2021), the Supreme Court allowed deportation of Rohingya in Jammu, stating that their continued presence was subject to executive discretion.

- However, in several High Court cases, including in Manipur and Delhi, courts have restrained authorities from deporting refugees without verifying safety conditions in Myanmar.

This current petition pushes the boundary further, seeking a blanket ban on prolonged detention without repatriation framework.

Human Rights Concerns: Detention Is Not Protection

Activists and human rights advocates argue that:

- Detention centers are overcrowded, lack basic medical facilities, and subject detainees to psychological trauma.

- There is no defined timeline for repatriation, meaning detainees are held indefinitely.

- Children born in India to refugee parents are being denied access to education and healthcare, violating India’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which India is a signatory.

Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia Director for Human Rights Watch, commented:

“Detention of Rohingya is not a solution—it is state-sponsored limbo. India must uphold its legacy as a shelter for the persecuted, not a prison.”

What Happens Next: A Test of India’s Constitutional Compassion

The Court has asked for:

- Detailed affidavits from the Ministry of Home Affairs and respective state governments

- Data on how many detainees are being held, for how long, and under what legal provisions

- Status of India’s dialogue with Myanmar on repatriation, given the political turmoil and military crackdown in that country

Statelessness Shouldn’t Mean Voicelessness

The Rohingya crisis in India isn’t just about refugees—it’s about how a nation upholds its constitutional values even in matters of security and immigration.

The Supreme Court’s decision will likely define whether India continues to be a soft-power nation rooted in Gandhian ideals of nonviolence and compassion, or whether it aligns more with security-first regimes that conflate identity with illegality.

Because dignity does not depend on citizenship. And human rights do not stop at the border.

comments