High Court Stays Facial Recognition-Based Surveillance by Civic Body: Raises Alarms on Privacy and Overreach

- ByAdmin --

- 15 Apr 2025 --

- 0 Comments

In a significant verdict that strengthens India’s evolving digital rights jurisprudence, the Delhi High Court has stayed the implementation of facial recognition-based surveillance by the North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC). The court cited constitutional concerns regarding privacy, lack of legislative backing, and absence of citizen consent as grounds for the temporary injunction.

This judgment is a major milestone in the ongoing debate between state surveillance and the right to privacy in India, especially in the absence of a comprehensive data protection regime.

Background: NDMC’s Smart Surveillance Rollout

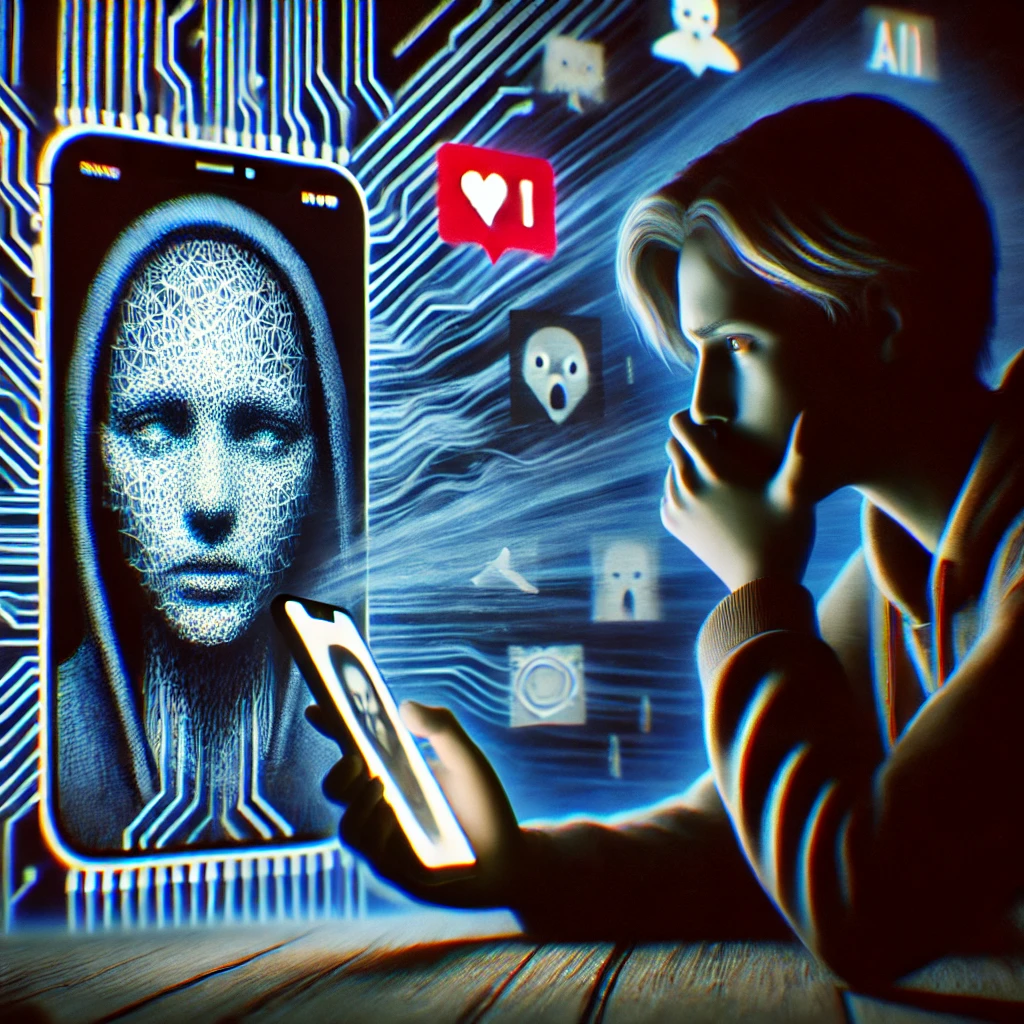

In early 2024, NDMC initiated a pilot project to install high-definition CCTV cameras embedded with facial recognition technology (FRT) in key public zones including:

- Commercial markets

- Metro stations

- Municipal parks

- Entry points to NDMC schools and hospitals

The stated objectives were to:

- Track habitual offenders and pickpockets

- Monitor school children and ensure attendance

- Aid in civic safety and enforcement

However, digital rights groups, local residents’ associations, and privacy activists challenged the move, alleging it lacked:

- Statutory basis

- Public consultation

- Data protection safeguards

- Oversight or redressal mechanisms

The Petition and Grounds for Challenge

The petition, filed by People for Digital Liberty, argued that:

- The FRT deployment violates the fundamental right to privacy as laid out in the Puttaswamy judgment (2017)

- It subjects residents to constant biometric surveillance without consent or due process

- NDMC has no legal mandate under the Delhi Municipal Act to collect or store biometric identifiers

- There is no clarity on where the data is stored, for how long, and who can access it

- Such projects create a chilling effect on civil liberties, including freedom of expression and movement

High Court’s Observations

In its interim order, the Delhi High Court stated:

“Any surveillance system that captures and processes biometric information such as facial data must be rooted in a valid legal framework, guided by necessity, proportionality, and accountability.”

The court further noted:

- The absence of parliamentary or state legislation to regulate FRT

- No demonstrable proportional justification for using FRT over other means of law enforcement

- The lack of public awareness and transparency about data usage

- Concerns over algorithmic bias, especially in densely populated areas with marginalized communities

As a result, the court stayed further installation and usage of FRT-enabled surveillance until the NDMC:

- Justifies the necessity and proportionality of the system

- Produces a clear privacy impact assessment (PIA)

- Demonstrates adherence to evolving constitutional standards of digital governance

Why This Matters: Legal and Constitutional Impact

1. Facial Recognition Is an Unregulated Frontier

Despite being used by police forces, metro authorities, and airports, India has no dedicated law to regulate FRT. This case sets precedent that executive decisions alone cannot justify biometric surveillance.

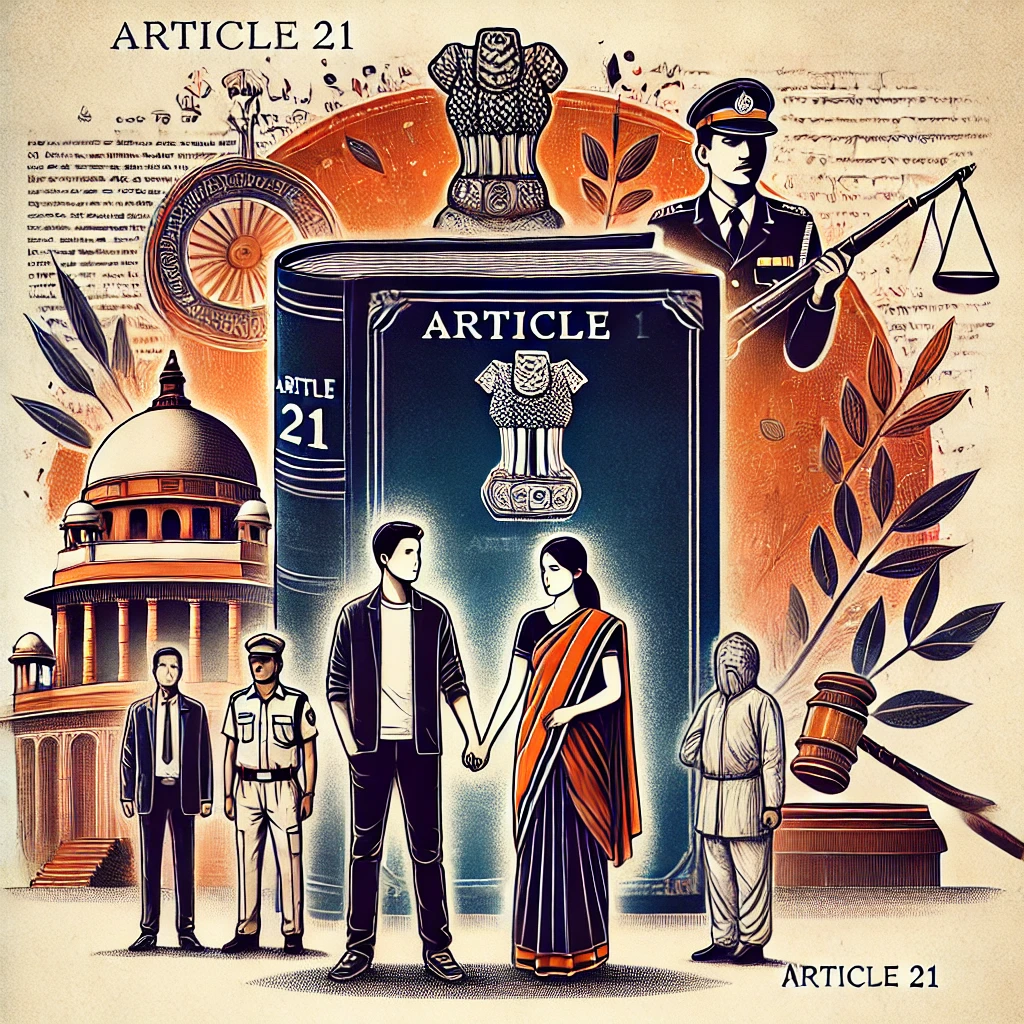

2. Upholding the Puttaswamy Principles

The judgment reaffirms the three-part test laid down in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India:

- Legality (backed by law)

- Necessity (for a legitimate state aim)

- Proportionality (least intrusive means)

FRT usage by NDMC failed on all three fronts.

3. Checks Against “Smart” Overreach

The court also cautioned against uncritical adoption of surveillance tech under “Smart City” projects and asked for a technology-agnostic assessment of civic needs.

Global Context and Comparisons

Facial recognition surveillance has faced increasing legal scrutiny worldwide:

- European Union proposed a ban on real-time FRT in public spaces under the AI Act

- San Francisco and Boston have passed municipal bans on FRT use by government bodies

- In the UK, courts ruled that police use of FRT without sufficient safeguards was unlawful

India’s case, however, is complicated by the absence of an enforceable data protection law, which leaves biometric data vulnerable to misuse or leaks.

Reactions from Stakeholders

a. Civil Society

Digital rights groups like Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) and SFLC.in have called the verdict a landmark protection against invisible surveillance.

b. Government Response

NDMC officials have claimed the system was intended to enhance public safety and would not be used for profiling. They have been directed to submit an affidavit outlining:

- Data usage policies

- Technical vendors involved

- Role of private contractors and storage protocols

c. Tech Industry

Companies supplying FRT tech have raised concerns over project halts, asking the government to frame clear compliance guidelines so innovation can proceed legally.

Next Steps and Broader Implications

The case is expected to resume in mid-2025, with expert inputs sought from:

- The Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY)

- The Delhi State Data Protection Cell

- Independent privacy and AI ethics scholars

It may eventually lead to the drafting of model state-level laws on biometric surveillance, feeding into the Data Protection Act’s regulatory framework once fully implemented.

A Pause That Protects Privacy

The Delhi High Court’s stay on facial recognition-based surveillance sets a powerful precedent—that public safety cannot come at the cost of constitutional privacy. It affirms that technology is not neutral, and that citizens deserve clarity, consent, and control over how their faces and data are used.

As India races to digitize its cities, this ruling sends a clear message: You can wire the streets—but only if the law walks with you.

0 comments