Missouri Code of State Regulations Title 18 - PUBLIC DEFENDER COMMISSION

Missouri Code of State Regulations – Title 18: Public Defender Commission

The Public Defender Commission in Missouri regulates the state’s public defender system. Title 18 CSR (Code of State Regulations) provides administrative rules for:

Eligibility for Public Defender Representation

Individuals charged with felony offenses, certain serious misdemeanors, parole/probation violations, or appeals who cannot afford private counsel are considered “eligible persons.”

Appointment and Duties of Public Defenders

Public defenders are assigned by courts to represent eligible defendants.

They must provide competent legal counsel and maintain professional ethics.

Fees and Reimbursement

Eligible defendants may be required to pay a nominal fee if they are able.

Fees vary based on the type of case and are set in regulation.

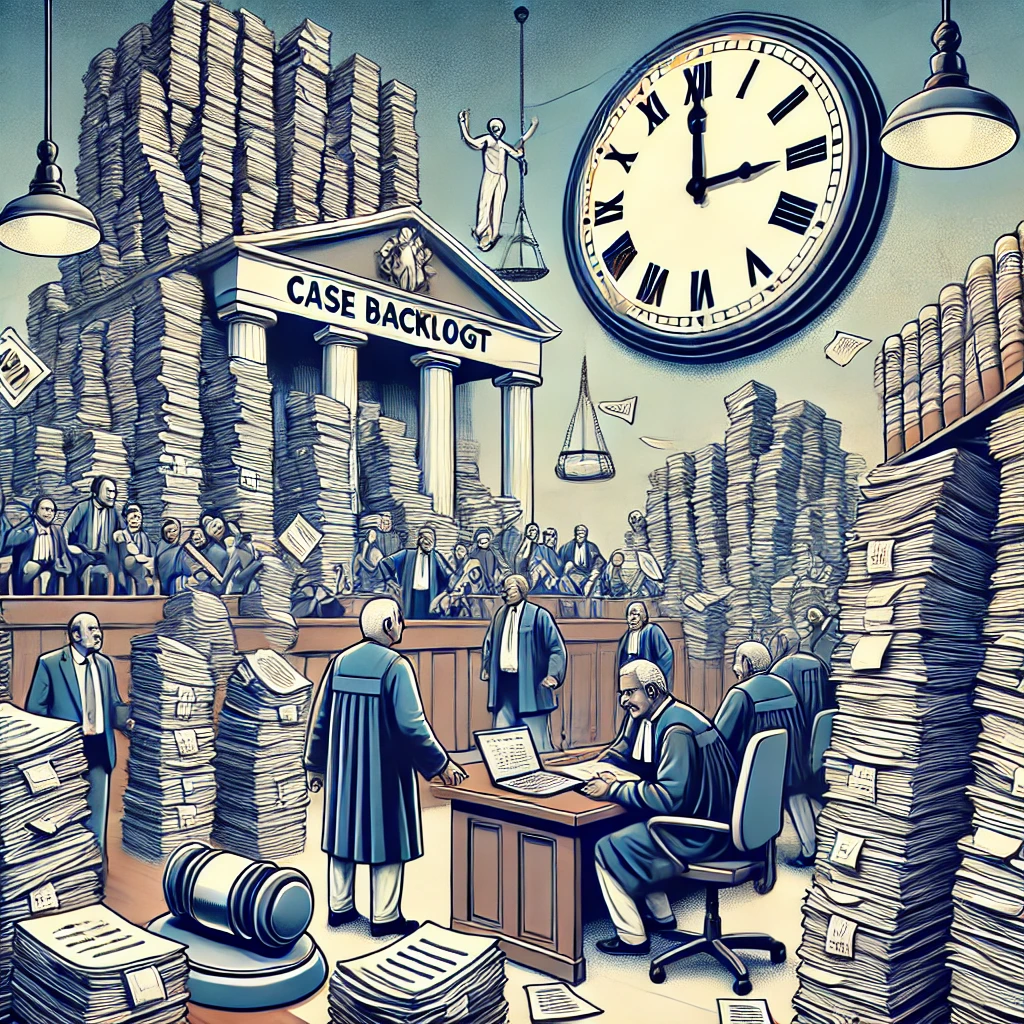

Caseload Limits and Administrative Procedures

The Commission may establish caseload limits to ensure effective representation.

When offices are overloaded, regulations allow limits on new case appointments to maintain quality of service.

Limits on Private Practice

Public defenders are restricted from certain private practices that could conflict with their duties.

Key Cases Related to Title 18 and Public Defender Representation

These cases illustrate how Missouri courts interpret and enforce Title 18 regulations and constitutional rights related to public defenders.

Case 1: State ex rel. Missouri Public Defender Commission v. Pratte (2009)

Facts:

A trial court appointed the public defender’s office to a defendant despite the office having reached its maximum caseload under Title 18 regulations.

Issue:

Can a trial court require a public defender to accept a case when the office is already overloaded?

Holding:

The Missouri Supreme Court held that the public defender office could lawfully refuse the appointment if it exceeded established caseload limits.

Significance:

Confirms that caseload limits are legally binding and serve to ensure effective assistance of counsel.

Emphasizes that the constitutional right to counsel includes quality, not just nominal assignment.

Case 2: Missouri v. Frye (2012, U.S. Supreme Court)

Facts:

Defense counsel failed to inform the defendant of a formal plea bargain, which could have reduced his sentence.

Issue:

Does the Sixth Amendment guarantee effective assistance of counsel in the plea bargain process?

Holding:

The Court held that failing to communicate a plea offer constitutes ineffective assistance if it prejudices the defendant.

Significance:

For Missouri public defenders, even with proper appointment under Title 18, failing to communicate plea offers violates constitutional rights.

Highlights the overlap between administrative regulations and constitutional obligations.

Case 3: Barton v. State (2016)

Facts:

The defendant challenged the effectiveness of post-conviction counsel provided by the public defender office.

Issue:

Does Title 18 guarantee effective counsel in post-conviction proceedings?

Holding:

The court ruled there is no constitutional right to effective counsel in post-conviction proceedings, although counsel may be appointed.

Significance:

Differentiates between trial representation (where effectiveness is constitutionally required) and post-conviction assistance (where administrative appointment is discretionary).

Case 4: Ward v. State (2025, Missouri Court of Appeals)

Facts:

Significant delay occurred between the trial court’s order to appoint a public defender and the actual notification to the defender’s office.

Issue:

Does such a delay invalidate the appointment or compromise the defendant’s rights?

Holding:

The court ruled that the appointment only became effective upon actual notification; the delay did not invalidate the appointment.

Significance:

Highlights the importance of timely communication and procedural compliance in public defender assignments.

Case 5: Public Defender System Funding and Caseloads (2009, Systemic Context)

Facts:

Public defender offices in Missouri were overloaded due to high demand, potentially affecting the quality of representation.

Issue:

Can regulations under Title 18 limit appointments to prevent overburdening without violating defendants’ rights?

Holding:

The Missouri Supreme Court upheld caseload limits, emphasizing that forcing representation beyond capacity could compromise effective counsel.

Significance:

Title 18 regulations allow systemic flexibility to maintain quality representation, balancing statutory duty, constitutional rights, and practical constraints.

Case 6: Strickland v. Washington Applied in Missouri Context

Facts:

Though not a Title 18 case, Strickland principles are routinely applied in Missouri. Defendants claim ineffective assistance when public defenders fail to provide competent counsel.

Holding:

Courts assess both deficient performance and prejudice to the outcome.

Significance:

Missouri Title 18 cases reference Strickland to ensure public defenders meet constitutional performance standards, not just regulatory compliance.

Key Takeaways

Quality Over Quantity: Caseload limits exist to preserve effective assistance.

Constitutional Standards Apply: Title 18 compliance alone does not satisfy the Sixth Amendment.

Procedural Compliance is Critical: Timely notifications and proper assignment affect validity.

Systemic Challenges Recognized: Courts acknowledge overloads and provide regulatory relief while balancing defendants’ rights.

Differentiation Between Trial and Post-Conviction: Title 18 ensures trial representation, but post-conviction counsel does not guarantee effectiveness.

comments